What We Forget When We Rush to Understand?

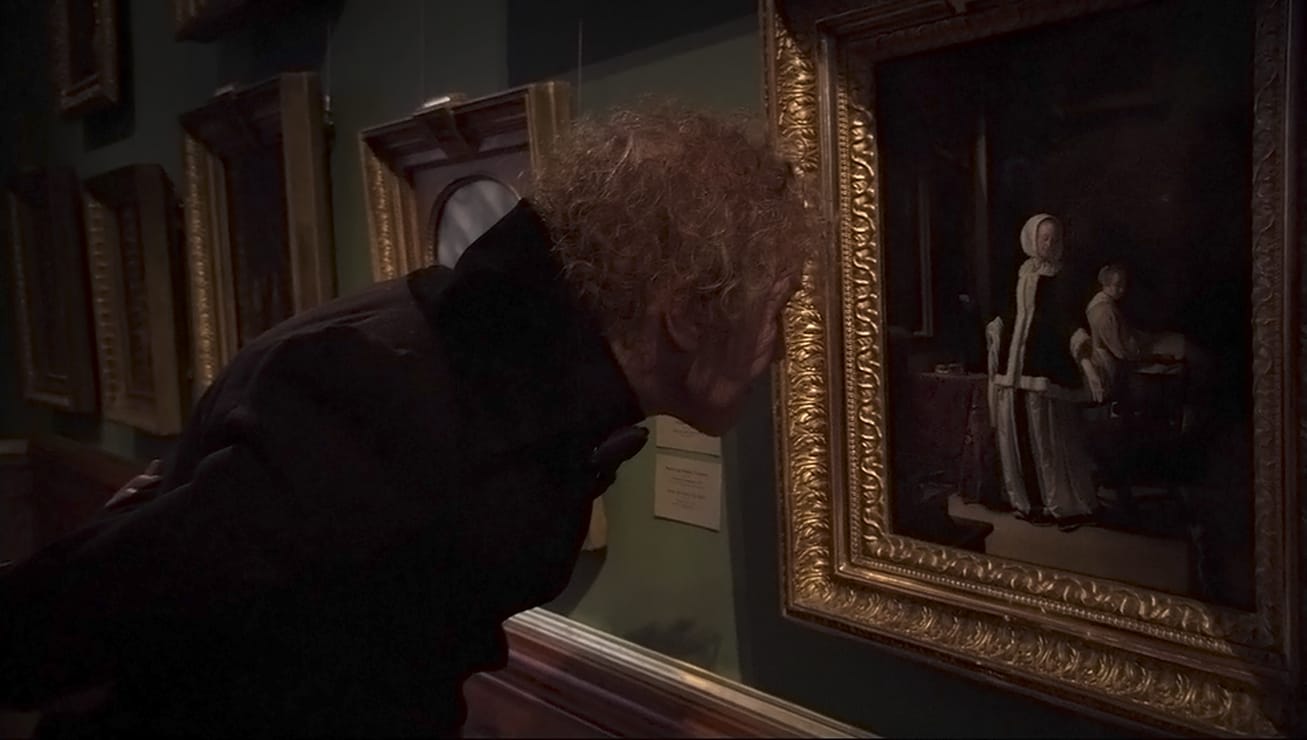

There is a particular violence in our need to make sense of everything too quickly. We see a painting and ask, What does it mean? as if meaning were a coin we could pocket and carry away. We step into a cathedral and demand to know how it was built, how long it took, who paid for it, why the arches rise the way they do. As though by gathering facts we can possess the place, and move on.

But isn’t there a kind of understanding that only arrives if you wait for it? The kind that slips in quietly, after you’ve stood a long time before a canvas and stopped trying to explain why a single brushstroke feels alive. Or after you’ve wandered beneath stone vaults and let the chill air settle on your skin, listening for something you can’t name.

Why do we find it so hard to let mystery be?

A face in a painting. A wall in a ruin. A fragment of a film you half-remember from childhood. We rush to name them, to fit them into categories, to file them away in memory as understood. But maybe there are things that resist this neatness. Maybe there are questions that aren’t meant to be solved in the first instant.

Have you ever stared at an old photograph so long it seemed to move? Or watched a film where the silence between words said more than the dialogue itself? There is a trembling there, a refusal to settle, as if the work were asking you to linger—not because it wants to be difficult, but because it holds more than one truth.

In literature too, the most powerful lines are not the ones we immediately grasp, but the ones that haunt us later, that return unbidden when we are falling asleep or gazing out a train window. Some truths are too large, too intricate, to be caught at once.

History itself unfolds like this. Layer upon layer, fragments upon fragments. An artifact dug from the earth can tell a dozen stories, each one contradicting the last. And still we are tempted to rush to a single, clean narrative. What happened? we ask. Who was right? Who was wrong? But time does not answer so easily.

Perhaps understanding is not a moment of sudden light but a slow accumulation of shadows and textures, like the patina on bronze or the wear on a marble step. Perhaps it is not something to be seized but something to be invited, the way music invites silence to give it shape.

What if we stopped asking, What does this mean? and began asking,

What happens if I stay here a little longer?

What if we allowed ourselves to be confused, unsettled, even bored for a while? What might emerge in that space?

There is no urgency in a tree growing, or in the way light shifts across a room at dusk.

Why, then, do we demand that we understand ourselves, and the world, all at once?

Maybe wisdom is not about speed but about attention. Maybe it lives in the moment. Maybe we could stop rushing and finally allow ourselves to understand.